The first ice skating report: London 850 years ago

- London On The Ground

- Dec 21, 2024

- 5 min read

William FitzStephen wrote the world’s earliest description of ice skating in around 1174.

Londoners and visitors enjoying outdoor ice rinks this December, such as the one at Somerset House, are following a centuries-old tradition.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

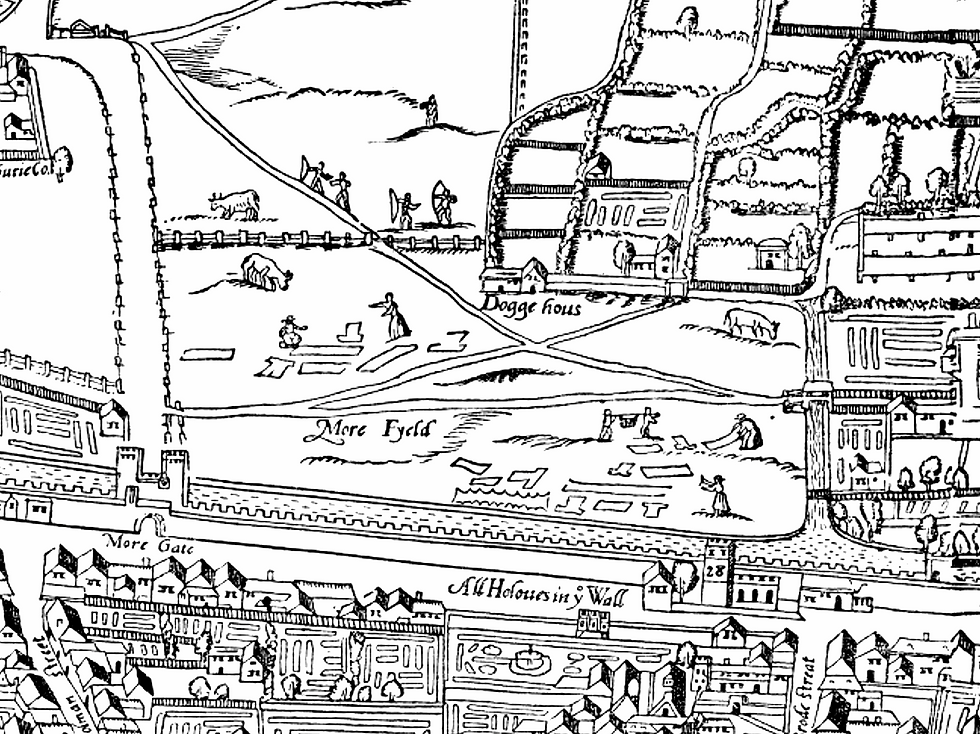

William FitzStephen, a 12th century native of London, described ice skating in Moorfields. This was a marshy area just outside the City wall, where Moorgate tube station and Finsbury Circus are now. Moorfields remained marshy until it was drained more than 400 years later, in the early 17th century.

Moorfields was used for drying and bleaching linen and other cloths, and also for archery practice, until Tudor times. These activities (and a dog house) are depicted in the Civitias Londinum, a map from around 1560.

But let’s return to 12th century London and the account by FitzStephen, a cleric who had worked as a clerk for Thomas Becket. His account, originally written in Latin, was published in an English translation in John Stow’s 1598 book The Survey of London (see also my post on Smithfield for his account of the livestock market there).

“When that great marsh which washes the walls of the city on the north side is frozen over,” he wrote, “the young men go out in crowds to divert themselves upon the ice.”

The level of skill and equipment was variable, FitzStephen tells us. Some people would simply run along the ice in their shoes and then, with their feet apart and their bodies turned sideways, “slide a great way”.

Others would “make a seat of large pieces of ice like mill-stones”, to be drawn by “a great number of them running before,… holding each other by the hand”.

This sounds a bit haphazard: “if at any time they slip in moving so swiftly, all fall down headlong together.”

Those with greater expertise would use “the shinbones of some animal” as a rudimentary form of skate.

The use of animal bones for skates has a long history, appearing in Finland around 3,000 years ago. Finland had many frozen lakes and skates were originally used for transporting people and goods, rather than for recreation.

Evidence of similar equipment can be found in historical records in other parts of Europe - including Scandinavia, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands - from the eighth century.

Skaters bound the bones, filed to a taper at the front end, to the underside of their shoes or boots with leather straps. The oily surface of bones helped them to glide smoothly on the ice.

Unlike modern ice skates, bone skates had no sharp edge and so they could not be used to gain traction. Instead, FitzStephen tells us that they took “in their hands poles shod with iron”, which they used to propel themselves “with as great rapidity as a bird flying, or a bolt discharged from a cross-bow”.

This would have required a huge amount of effort and, although the smooth bone allowed a very enduring glide on smooth ice, the speeds achieved were very tame compared with what is possible today.

It has been estimated that bone skaters could reach around 5 mph (8 kph), positively snail-like versus the more than 30 mph (50 kph) achieved by modern speed skaters.

Back in 12th century London, FitzStephen wrote that sometimes young men would use the frozen marsh outside the City wall as a slippery tilt yard, pitting themselves against one another in an icy form of jousting.

Two skaters would rush headlong towards each other from a great distance and use their poles as lances to strike each other. The result could be painful:

“…either one or both of them fall, not without some bodily hurt: even after their fall they are carried along to a great distance from each other by the velocity of the motion; and whatever part of their heads comes in contact with the ice is laid bare to the very skull. Very frequently the leg or arm of the falling party… is broken.”

William FitzStephen explained the mentality behind these clashes with a 12th century version of 'boys will be boys':

“…youth is an age eager for glory and desirous of victory, and so young men engage in counterfeit battles, that they may conduct themselves more valiantly in real ones.”

Notably absent from the FitzStephen account is any mention of women or girls. However, a Dutch woman would later become the patron saint of ice skating.

St Lidwina (1380-1433) was badly injured by an ice skating accident at the age of 15. Possibly as a result of multiple sclerosis and the accident, she became more and more disabled until her death at the age of 52. She was known for fasting and as a healer and is also patron saint of chronic pain and of her hometown of Schiedam.

Metal blades attached to wooden skates first started to appear in the Netherlands in the 14th century, but only for those who could afford them.

Metal skates only came to England after Charles II and his brother James returned from exile in the Netherlands, at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. On 1 December 1662, diarist John Evelyn described “the wonderful dexterity of the skaters on the canal at St James by divers gentlemen with skates, after the manner of the Hollanders”.

On the same day, diarist Samuel Pepys described skating as “a very pretty art”. Two weeks later he again witnessed skating at St James’s Park. There, he wrote, the Duke of York (later James II), “though the ice was broken and dangerous, … slides very well”.

It was not until 27 December 1830 that London’s first skating club opened, on The Serpentine in Hyde Park at a time when ice skating was popular among the higher echelons of British society.

In the 1840s, ice rinks were constructed in London using artificial ice made from hog’s lard and salts, but the public soon lost interest (not least because of the smell of the ‘ice’).

Advances in refrigeration technology led to the world’s first mechanically frozen ice rink opening in London a few decades later. A vet and inventor named John Gamgee opened the Glaciarium off the King’s Road, Chelsea, on 7 January 1876. The members-only facility was aimed at the wealthy, both men and women. It had an orchestra gallery and views of the Swiss Alps on the walls.

Ice skating had been open to anyone in the 12th century, but it later became more exclusive. Today, recreational ice skating is affordable for most Londoners, whether in local leisure centres and other year-round indoor rinks, or at the winter-only outdoor venues.

It is also generally less violent than it occasionally could be in medieval times, possibly because it doesn't only involve young men.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

Comments