Islington Cattle Market: lost secret of Essex Road

- London On The Ground

- Jul 21, 2024

- 6 min read

The challenger to Smithfield closed in 1837 after less than a year.

A couple of years ago, at one of the excellent exhibitions at the London Metropolitan Archives, I was stopped in my tracks by a copy of a 19th century map of Essex Road and its surroundings.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

What struck me about the map was a dark, almost square, feature labelled 'Islington Cattle Market' just off the Lower Road (as that part of Essex Road was then called).

I had known this part of Islington for almost 30 years and had never heard of this market before.

I knew that a cattle market had been opened in 1855 less than two miles to the west of this spot in what is now Caledonian Park (where the market's clock tower still stands) but knew nothing of its short lived precursor on a site that has long since been built over.

Islington Cattle Market was opened on what had been a rural site in April 1836 and closed very soon afterwards in 1837. It was intended as an alternative to the centuries-old livestock market at Smithfield in the City of London.

It was built by Mr John Perkins, a landowner from Bletchingley in Surrey, on 15 acres to the southeast of the Lower Road acquired from Thomas Scott. He began the project in November 1833 and spent £100,000 to complete it.

The site had been part of a brickfield belonging to Scott. Brickfields were a feature in Islington in the transition of London's rural surroundings into built-up urban areas during the 19th century.

Bricks were made from clay dug from underneath what had been fields and pastures in order to build houses in the same area. Once the clay was exhausted and houses were built, the process of urbanisation then ate up more fields further into the countryside.

It seems that John Perkins was motivated by a desire to improve conditions for the public in areas leading to Smithfield and also for cattle, sheep and pigs held at the market.

Smithfield Market had been established to sell livestock at least as early as the 12th century, and probably much earlier. It was located in open fields northwest of the City walls and just beyond St Bartholomew's Hospital.

By the 19th century London's built-up area had grown to surround Smithfield Market and its animal pens. Drovers had to drive cows, sheep, pigs and other animals to Smithfield along busy London streets full of businesses, houses and traffic.

Conditions for animals at the market were inhumane and unsanitary, while the noise, mess and congestion were hugely problematic for the human population.

Thomas Carlyle, a very influential Scottish writer and philosopher (who appeared in my post about Ford Madox Brown's 1865 painting Work) described Smithfield Market in 1824, referring to:

"…thousands of graziers, drovers, butchers, cattle brokers with their quilted frocks and long goads pushing on the hapless beasts; hurrying to and fro in confused parties, shouting, jostling, cursing in the midst of rain and shairn and braying discord such as the imagination cannot figure…"

('Shairn' is a Scottish word, whose Anglo Saxon translation also begins with 'sh'.)

Writing in the following decade, around the time that the new market in Islington was closed, Charles Dickens described Smithfield Market in his novel Oliver Twist.

“The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney-tops, hung heavily above… Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a mass; the whistling of drovers, the barking dogs, the bellowing and plunging of the oxen, the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs, the cries of hawkers, the shouts, oaths, and quarrelling on all sides; the ringing of bells and roar of voices, that issued from every public-house…and the unwashed, unshaven, squalid, and dirty figures constantly running to and fro, and bursting in and out of the throng; rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene, which quite confounded the senses.”

A notice announcing the launch of the new Islington Cattle Market in 1836 declared that it would "be found to possess greater advantages for the sale, protection and sheltering of Cattle than any other Market in the Kingdom”.

"Special care has been taken in the selection of the spot, in order that the great objection of driving cattle through the streets might as much as possible be avoided."

It boasted that the market was "spacious" and "airy" so that animals could be viewed much more conveniently than at Smithfield. Further "water is so disposed that every Beast may drink at pleasure".

Animals would be "well sheltered, foddered & watered, carefully watched, and have the advantage of resting quiet, and improving in condition until the Market commences".

The public would "derive great benefit" as the streets of London would "in great measure be cleared from the disgusting and brutal exhibitions too often witnessed in Cattle passing along".

The people of Islington were only too familiar with such exhibitions, since Upper Street - Islington's main road - formed part of the principal route to Smithfield Market from all over the country.

Importantly, too, the new market meant that the Sabbath would "not be profaned". This was a reference to Smithfield's use of Sunday to sort the animals in preparation for the Monday market, a pattern that would be discontinued at the Islington location.

Other markets that had been swallowed up by London's dramatic spread in the 19th century had already been re-established away from centres of population.

The Islington Cattle Market cost £100,000 and had capacity for 7,000 cattle, 500 calves, 40,000 sheep and 1,000 pigs.

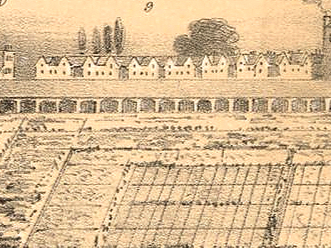

The Architectural Magazine reported in June 1836 that there were three "wide and spacious approach roads" and "six handsome and convenient entrances", including a "splendid building" at the main entrance.

It included buildings for banking and money-taking and a meeting area for salesmen, graziers and others.

The site had sewers, a water supply with wind-powered pumps, abattoirs, an inn with stables for drovers, and cottages for market workers along the Lower Road.

However, even before it opened, Perkins' new cattle market was met with immediate and forceful opposition from vested interests.

Smithfield Market, the City of London Corporation and pub landlords in the City effectively made sure that it could not succeed.

In its first eight months of operation, the Islington Cattle Market achieved total sales of just 87,845 animals. This compared with Smithfield's sales of more than 1.1 million over the same period.

Closure was inevitable and came in 1837, less than a year after it opened, although the site continued in use for some time for cattle lairs (where cattle were rested on the way to Smithfield) and the occasional sale of livestock on a very small scale.

The market soon became derelict, but received renewed attention and hope in the late 1840s, when conditions at Smithfield were becoming so acute that alternatives were under more active consideration.

The buildings were even repaired and its facilities advertised once more in 1849, although John Perkins had died by this time.

The site was eventually auctioned in 1852, but acquired not by the City Corporation or anyone with an interest in its livestock facilities. Rather, it was sold to property developers, who soon built rows of brick houses on long and straight new streets.

That same year, the City Corporation acquired another site in Islington, at Cophenhagen Fields. There it built its new Metropolitan Cattle Market, opened in 1855 as a replacement for Smithfield, which closed as a livestock market in the same year (Smithfield re-opened in 1868 as an indoor meat market, but with no live animals).

John Perkins had indeed created a market with "greater advantages for the sale, protection and sheltering of Cattle", but he had made two mistakes.

One was to be ahead of his time. The other was to challenge the monopoly of the City of London Corporation and its Smithfield Market.

The site of Mr Perkins' Islington Cattle Market is now covered by Northchurch, Oakley, Englefield and Ockendon Roads and bordered by Essex Road and Southgate Road.

Only the former workers' cottages on Essex Road still stand. Above the shop fronts, added later, the distinctive Tudor-like triangular gables are unmistakeably those portrayed in the 1836 view of the market.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

Comments