Arsenal's Art Deco Highbury, Herbert Chapman and me

- London On The Ground

- Apr 20, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2024

The North London stadium was unique in football architecture, motivated by an innovative manager and inspiring generations of Arsenal players and fans.

Arsenal moved from south London to the Highbury area of Islington in 1913, taking a lease on the playing fields of St John's College of Divinity. The move was instigated by the club's chairman, Sir Henry Norris, a strong-willed and successful businessman with interests in property and construction, a Mayor of Fulham, Conservative MP and also chairman of Fulham Football Club.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

Highbury offered a larger potential fan base than was available around Arsenal's Woolwich home. Norris saw the move as a way to solve Arsenal's considerable financial problems, after proposals to merge or to ground share with Fulham were rejected by the FA.

A stadium was built at Highbury over the summer and opened for the first match of the 1913-14 season, a 2-1 win against Leicester Fosse on 6 September 1913. The architect, Archibald Leitch, also designed a number of other football grounds.

Under the terms of the lease with the College, the sale of alcohol and the staging of matches on Good Friday and Christmas Day were not allowed. However, 12 years into the 21 year lease, Arsenal bought the ground outright in 1925 under a deed of transfer signed by the Archbishop of Canterbury (a personal friend of Sir Henry's).

The College of Divinity remained at the southern end of the ground until a fire destroyed it at the end of World War II (Aubert Court flats are now on the site).

The stadium was completely rebuilt in the 1930s, a period when Arsenal dominated English football (winning five league titles and two FA Cups).

The Art Deco West Stand was opened in 1932, designed by architects Claude Waterlow Ferrier and William Binnie.

The East Stand, designed by Ferrier and Binnie in a style to match the West Stand, was officially opened on 24 October 1936, for a 0-0 draw against Grimsby Town. Sadly, Ferrier did not live to see this, as he died after being hit by a motor cycle in 1935.

The West Stand had capacity for 21,000 spectators, while the East Stand was designed for 10,000. However, the East Stand also had offices, dressing rooms, a board room, entertainment spaces and other facilities.

Innovations in the East Stand included a permanent broadcasting box, a TV control tower, a central control point to monitor flow through the turnstiles and a system for converting litter from the terraces into fuel to heat the dressing room and corridors.

The East Stand was also the only stand in the Highbury ground with a street frontage, on Avenell Road, which allowed the architects to display its Art Deco attractions to full effect.

The East Stand was Grade II listed in 1997. English Heritage's Senior Properties Historian described it and the West Stand in 1991 as "the grandest pieces of football architecture ever built in Britain with the single possible exception of […] Ibrox Park".

The highest ever attendance at Highbury was 73,295 on 9 March 1935, for a 0-0 draw against Sunderland. Improvements to the terraces had reduced the stadium's capacity to 57,000 by the 1980s. The introduction of seating only, with no standing areas, reduced the capacity to around 38,000 after 1993.

This proved insufficient for one of the leading football clubs in England and Europe. Expanding the capacity at Highbury was impossible due to its being surrounded on three sides by houses and flats and because the listed East Stand could not be demolished or substantially altered.

This eventually led to the move around the corner to a new ground, the Emirates Stadium, in 2006.

A residential development, called Highbury Square, preserved the exteriors of the old Arsenal Stadium, creating new flats inside. However, it demolished the North Bank and the Clock End, replacing them with new blocks of flats, and turned the pitch area into a garden.

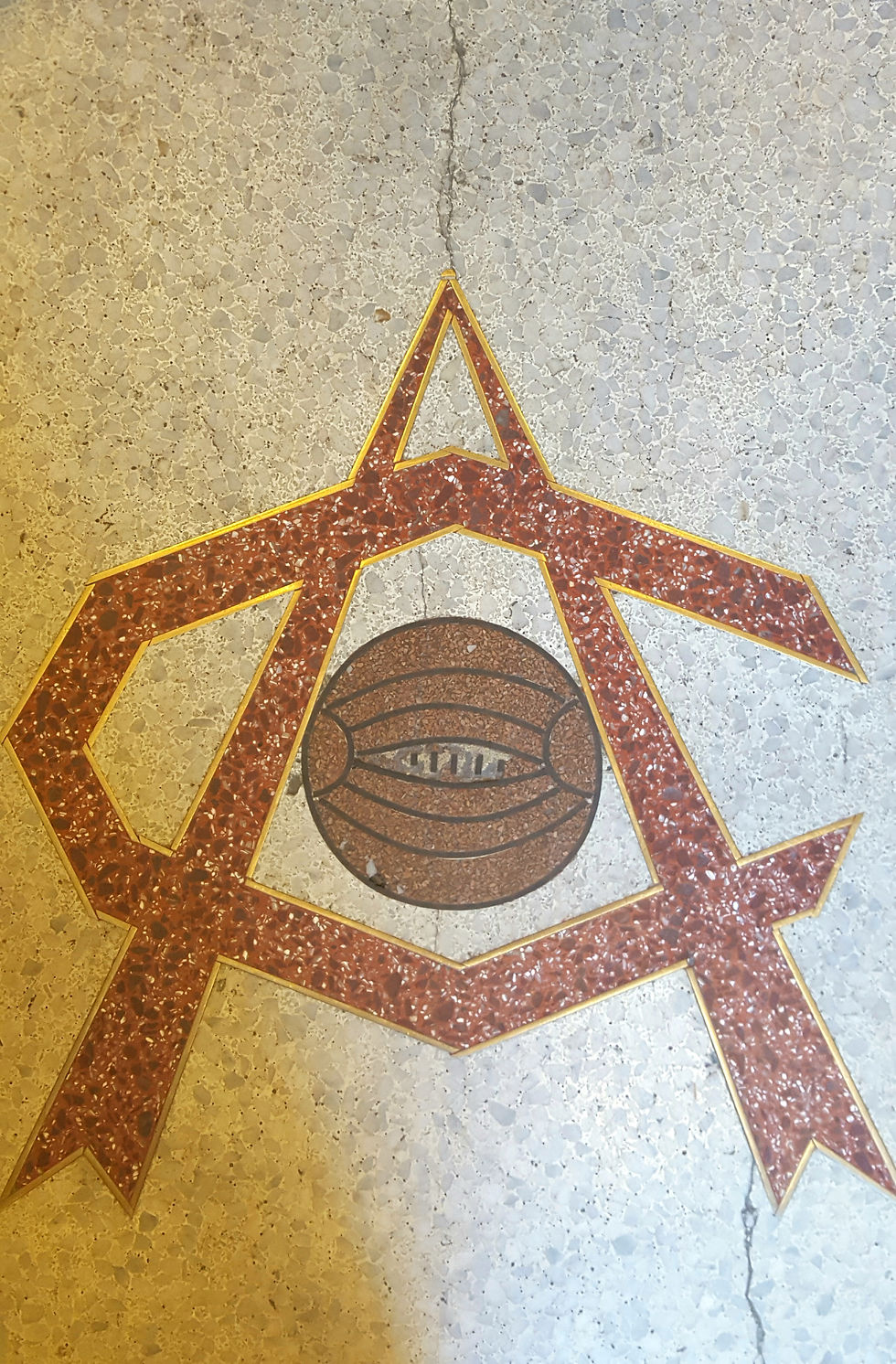

The palatial entrance to the East Stand contained the famed Marble Halls of Highbury, with marble walls, polished granite floors and a uniformed commissionaire on duty.

Now one of the entrances to the Highbury Square residences, it retains the red cannon inlaid into the floor and the 1934 marble bust of Herbert Chapman (by sculptor Jacob Epstein).

Chapman, a Yorkshireman, was Arsenal's manager between 1925 and 1934 and its most successful and innovative leader until Arsene Wenger. He was one of the first football managers to be fully in charge of team selection and the footballing side of the club, a departure from the time when the board was more active in such matters.

The Arsenal that he joined in 1925 was a club with no major trophies and which had struggled with relegation in the previous two seasons. By contrast, his previous club, Huddersfield Town, was England's most successful at the time. Chairman Sir Henry Norris brought Chapman to Arsenal, but did not witness his success. Norris was forced to resign in 1929 after the FA found evidence of financial irregularities.

Under Chapman, Arsenal won the FA Cup in 1930, followed by two league titles (1931 and 1933) and were on the way to the 1934 title when the manager died suddenly from pneumonia at the age of 55 on 6 January 1934. Two more league titles and one more FA Cup win followed in the 1930s under his successor George Allison.

Herbert Chapman was instrumental in the rebuilding of the stadium in the 1930s, not only to update its appearance, but also to improve its facilities for players and fans.

Chapman was a highly influential pioneer in many areas, including tactics, training techniques, diet and the use of physiotherapy. Several other innovations in football can also be traced to him.

The FA Cup Final of 1930 was the first in which both teams walked onto the pitch side by side, a tradition that continues to the present day. This was in recognition of Herbert Chapman's role as the current manager of Arsenal and former manager of Huddersfield Town.

Incidentally, Arsenal won that final 2-0 to take the club's first major trophy, while Huddersfield (under Chapman) had won three successive league titles and the FA Cup in the 1920s.

In 1933 Herbert Chapman added white sleeves to Arsenal's previously all red shirt to make it more distinctive.

Chapman was also an early advocate of signing foreign players and proposed a Europe-wide club competition decades before the advent of the European Cup.

Arsenal were the first top-flight team in England to play under floodlights, when they tried out the new illuminations in a friendly against Hapoel Tel Aviv on 19 September 1951. The stadium's floodlights had been incorporated into the design of the West and East Stands, avoiding the ugly towers used at many other stadiums.

It was Herbert Chapman's idea to install a clock in the stadium in 1930. A 45 minute clock, counting down the minutes of each half, was fitted at the back of the north terrace (called the Laundry End until the 1960s, when it became known as the North Bank). However, the FA feared it could usurp the referee's authority and so the clock was changed to a conventional timepiece.

The clock was moved to the south terrace (then called the College End) in 1935, after which it became known as the Clock End.

The original clock was placed on the outside of the new stadium in 2006, with a larger replica installed inside (also at the south end of the stadium).

In 1932 Chapman persuaded London Underground to rename the Piccadilly line's Gillespie Road station to Arsenal station (still the only tube station named after a football club). The close proximity of the station had been one of the factors in Sir Henry Norris's decision to move the club to Highbury in 1913.

Chapman and Arsenal were also involved in a number of other innovations in football, including live radio broadcasts of matches, numbered shirts, white footballs and rubber studs on boots.

Later, on 16 September 1937, parts of a game between Arsenal's first and reserve teams became the first live televised match anywhere in the world.

The Art Deco splendour of the Arsenal stadium was unrivalled in the football world and set new standards for both function and aesthetics. Together with the influence and ideas of Herbert Chapman, it inspired Arsenal to become one of the most successful clubs in the country, known not only for its achievements on the pitch but also for a sense of style, history and heritage.

My reason for writing this post now is a personal one, as it is exactly fifty years since my first visit to Highbury. My father took my sister, brother and me to a 2-0 win against Derby County on 20 April 1974 (goals from Alan Ball and Charlie George).

We were all much too small for the terraces, so we sat in the West Stand, from where we could see the players run out towards us from the tunnel in the East Stand. While more comfortable than the terraces, it was not too genteel to avoid the bad language and abuse hurled at the referee.

For an uncanny recreation of what my first experience of the Arsenal Stadium was like, just watch the scene in the Nick Hornby film Fever Pitch when the young Paul is first taken there by his father.

My dad had been taken to Highbury as a young boy by his father on 1 May 1948, the final day of Arsenal's league title winning season, witnessing an 8-0 win over Grimsby Town.

When I was growing up, and in my early adulthood, house moves were very frequent and did not include London. However, occasional visits to Highbury followed that first game, enough for it to become a kind of home from home, one of the few constants in my itinerant life.

When I moved to London in the 1990s, it seemed natural to live within walking distance of the Arsenal Stadium (which was always its official name, although almost everyone called it Highbury).

For the next 20 years or so I attended up to a dozen or more games every season. I was fortunate that this was a period of great success and wonderfully attractive football under Arsene Wenger, but it was also the stadium itself that lent me a feeling of belonging.

For a while after the old stadium closed, I continued to go to games at the Emirates, a very impressive and well equipped stadium. However, it just wasn't home, other priorities entered my life and I eventually stopped going.

I have no photographs of my first match at Highbury, but I do have the match programme, complete with my father's handwritten amendments to the team sheet on the back.

Click on any photo to enlarge

I have photographs of my last match at Highbury, which was the last game ever played at the old stadium, on 7 May 2006.

Arsenal defeated Wigan Athletic 4-2 (goals from Robert Pires and a hat trick from Thierry Henry), securing fourth place in the Premiership and qualifying for the Champions' League at the expense of local rivals Tottenham Hotspur. My dad came with me.

One of my most memorable times at Highbury was the second leg of the European Cup Winners' Cup semi final against Paris St Germain on 12 April 1994. Arsenal won with the only goal of the night, a header from Kevin Campbell. This made it 2-1 on aggregate and secured passage to the final against Parma, which also ended in the scoreline 1-0 to the Arsenal.

There is a painting inside the new stadium depicting that 1994 match at Highbury, by an artist called Joe Scarborough. It is a vibrant and evocative portrayal of the energy, colour and passion - and the art deco elegance - that I will forever associate with the Arsenal Stadium at Highbury.

This post is dedicated to the memory of Tony Wober (1939-2023)

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks, please click here.

What an interesting article! I love the bit about rubbish being recycled and used to heat the dressing rooms. The Joe Scarborough painting would make a lovely jigsaw puzzle. What an incredible person Herbert Chapman was. As was your father - he would have loved this post so much!